Shape fractal: technology of a smart systems

AL-1 Improving processes, change transitions, using the 6*6 reference framework

Explaining - optimizing, processing operations.

Improving business processes is an old topic. In technical change hypes often overlooked as the thing that really matters.

The decisions are boardroom responsibilities. The advices what to be improved is by looking at the shop floor.

🔰 Most logical

back reference.

Contents

| Reference | Topic | Squad |

| Intro | Explaining - optimizing, processing operations. | 01.01 |

| Why BPM | Why Engineering Organisations. | 02.01 |

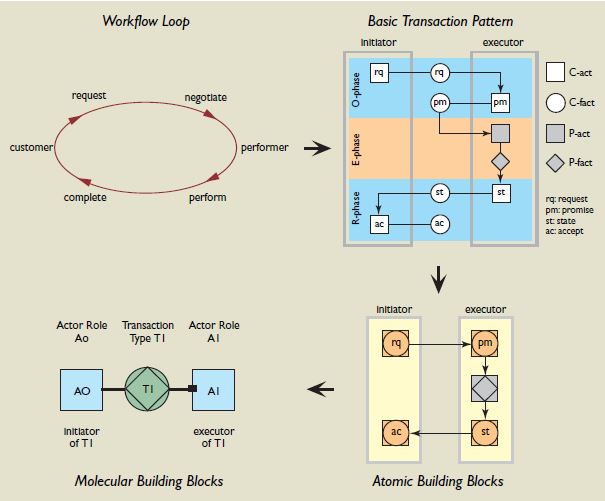

| initiator-executor | The process circle in engineering organisations. | 03.01 |

| Process Mining | Process Mining. | 04.01 |

| cycle BPM | Elementary process cycle. | 05.01 |

| What next | Inventing changing Operations. | 06.00 |

| | Combined pages as single topic. | 06.02 |

Combined pages as single topic.

🕶 data info types different types of data

🚧 info types different types of information

👓 Value Stream of the information product

👓 transform information Working cell

👓 bi tech Business Intelligence, Analytics

Progress

This chapter is partially fresh, partially converted. Topics are:

- 2019 week 42

- New Topic on improving designing a process

- Just doing BI is not the real goal. Going for the organizational process.

Why Engineering Organisations.

BPM - Business Process Modelling.

The model of a business has the goal of understanding the business so you can improve things.

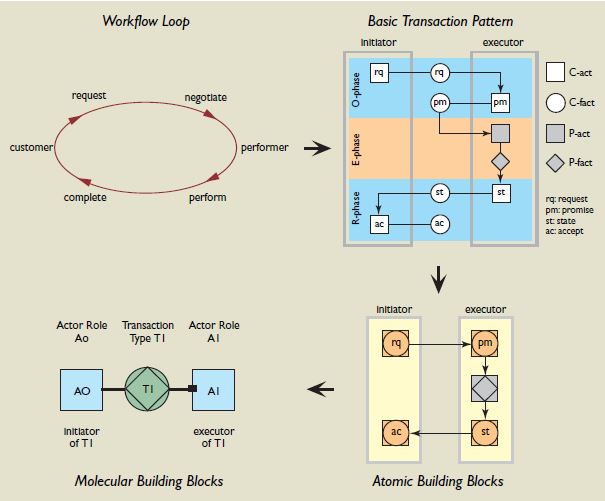

Demo - Design and Engineering Methodology for Organizations.

The first thing to be recognized is that organizations are designed and engineered artefacts, like automobiles and information systems. The distinctive property

of organizations is that the active elements are human beings, more specifically human beings in their role of social individual or subject.

...... only if one recognizes that the core of organization is in the coordination processes (the entering into and complying with commitments)

and not in the production processes, can one understand the operation of these kinds of organizations.

The deep structure of business processes (2015 Dietz) Interviews and Practitioner´s Publications

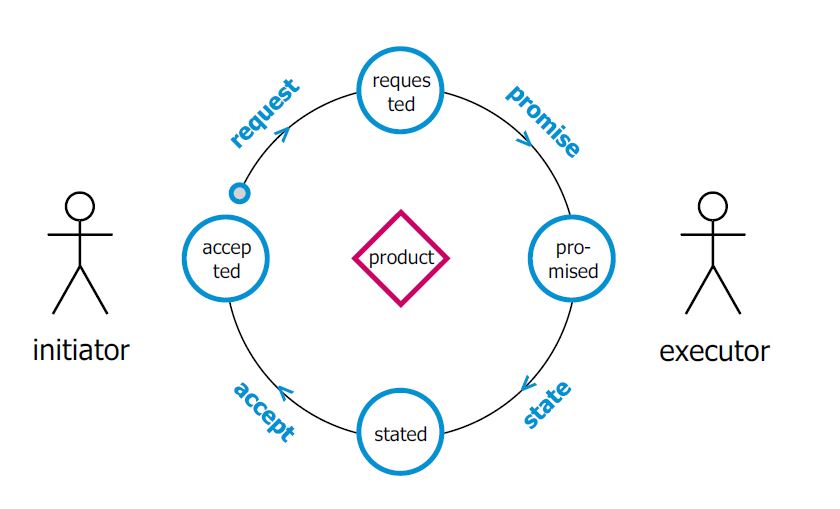

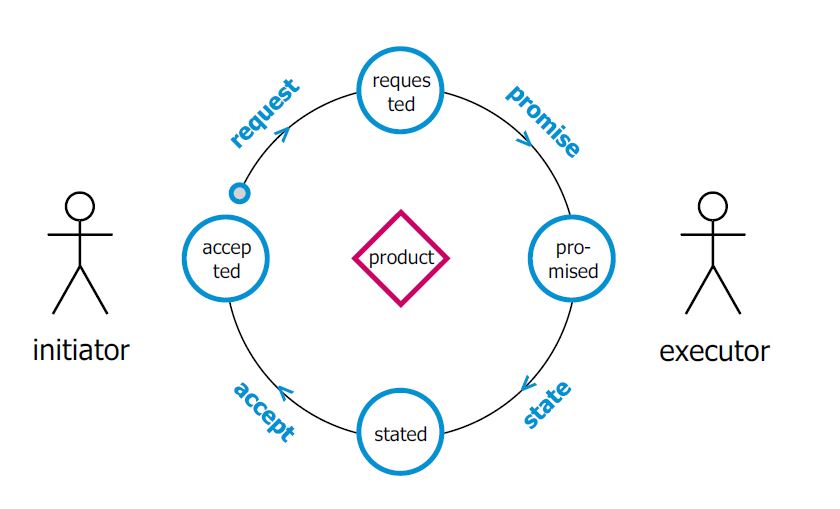

The process circle.

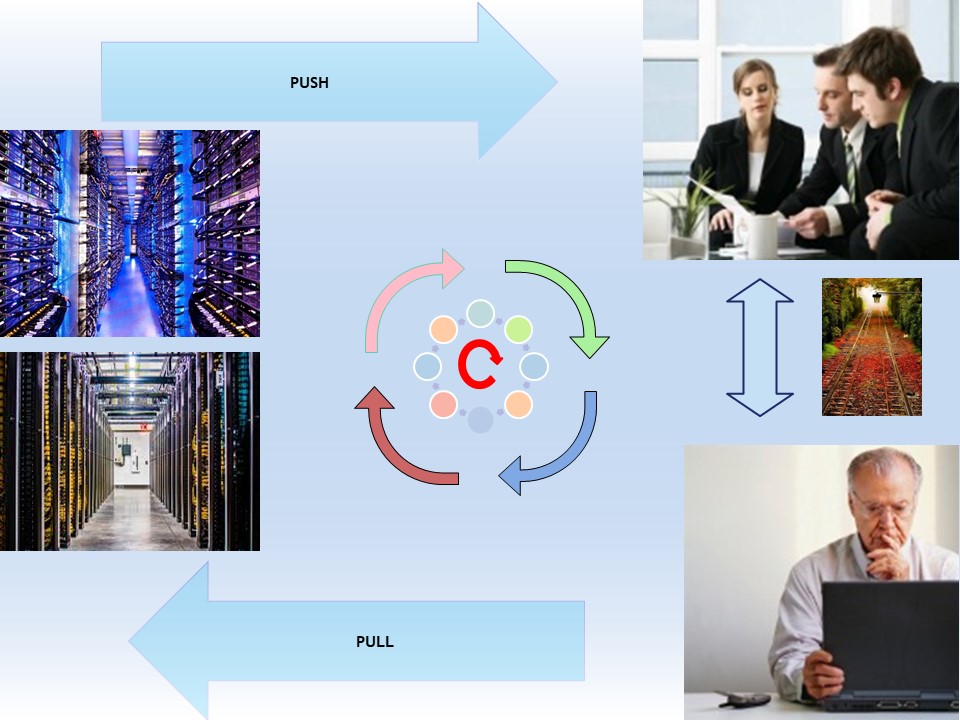

The demo figure is placing the customer at the left side, the executor right. The product flow is right to left where it is normal left to right.

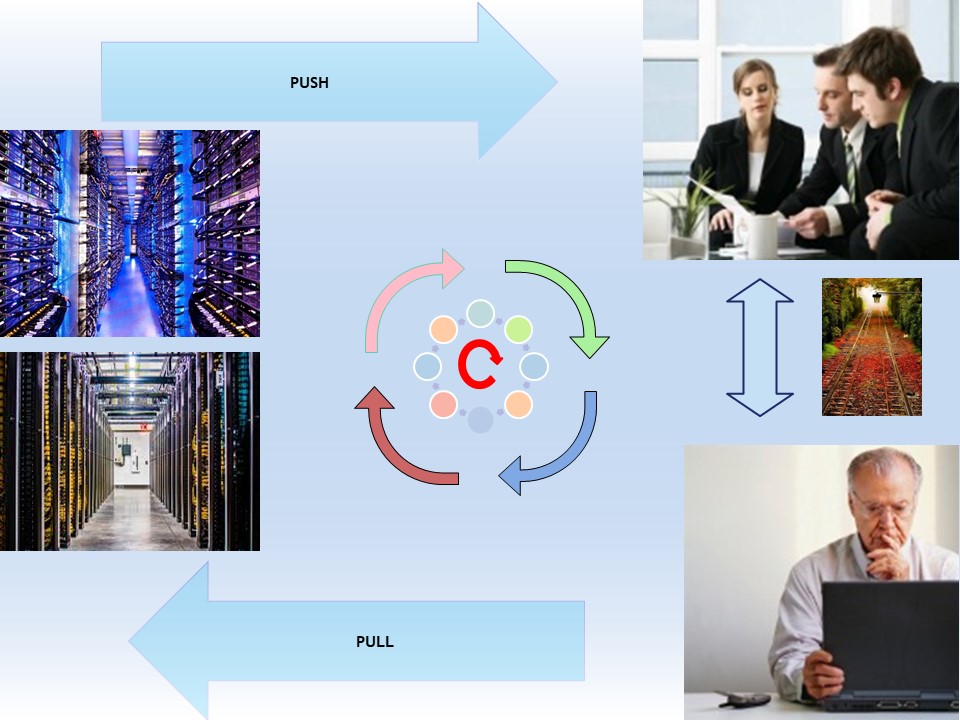

Personal I prefer to stick with an left to right flow of the product delivery. This is coming back in the value stream. The Pull request is right to left and the Push delivery Left to Right.

The process circle in engineering organisations.

Words are used to explain the engineering to others. The vocabulary for managing structuring organisations is not consistent.

Words for even simple processes have that diffusion in perspectives.

The glossary by words is not consistent.

| 🤔 🎭 | -💰- | ⚙ ⌛ |

| customer | | delivery |

| requestor | | performer |

| request | | provide |

| initiator | | executor |

| Pull | | Push |

| service request | ---- | Service provider |

Essential the same,but different words.

It is about the intentions with those words. The chosen word and how they are written is irrelevant.

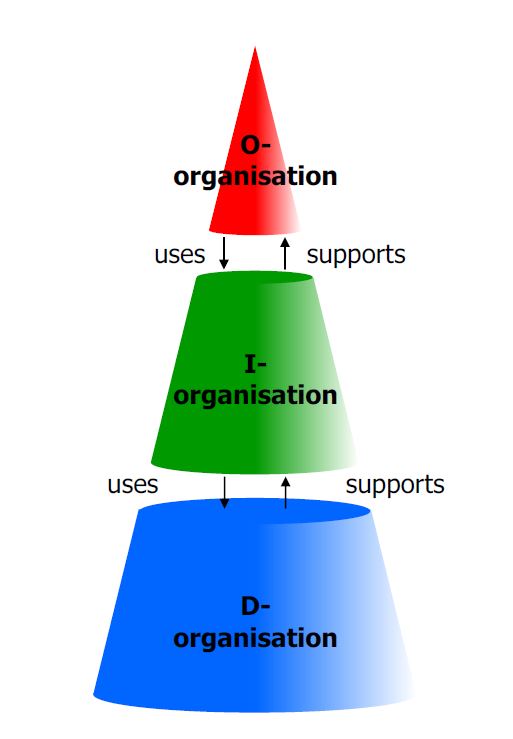

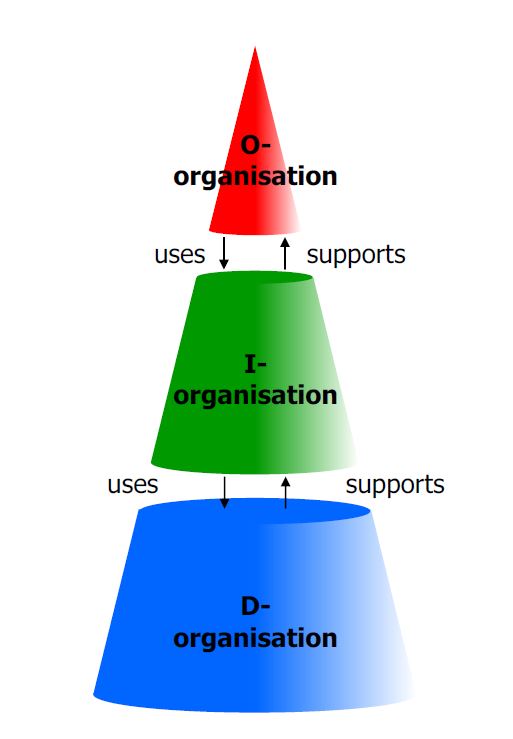

Operation, Information, Documentation

With DEMO several types of inforamtion are defined.

- The clear value O-Organisation.

- The associated I-organisation on what is happening.

- D-organisation what is required as documentation.

This is a limited list if inforamtions types, there are many more.

- Who has excuted the process, when and how long did it last.

- Which tools were used, configured by type location version.

- The state of used tools going into another process of maintaining supporting those for the main proces.

Requestor Informing by predictive, prescriptive reporting.

The requestor at the right side-up with delegated specfications what to be deleivered right side down.

Who is who in the execution, product creation, operation, is not visible. The shop floor is were the money is gnerated but too often getting ignored.

That left side is split up in preparation & information documentation and the operational delivery tn

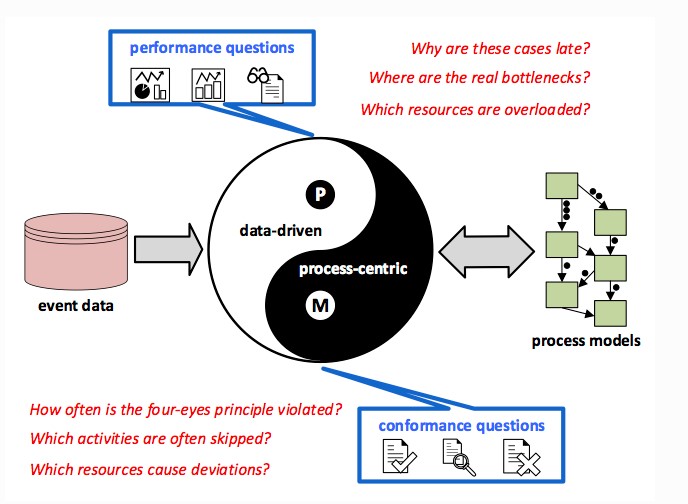

Process Mining.

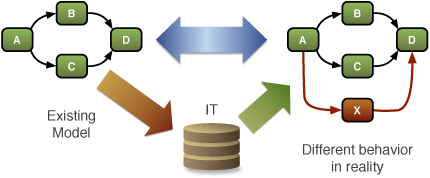

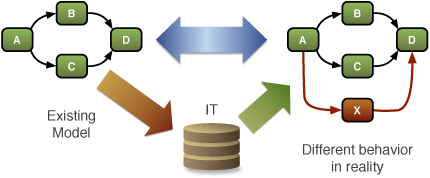

Improving something is requiring understanding of the existing situation. Improving processes not really knowing what is going and than mine those processes.

Big data - IOT 4.0

The hype (2019) is in getting data. To exagerate data is allabout, store data in datalakes.

The expectation is that by some magic (big data , data science) processes will improve automagically.

The reality is that impeovemetn of processes is hard work, sometimes many years are needed to achieve goals.

Reverse engineering processes.

Process mining techniques allow for extracting information from event logs.

For example, the audit trails of a workflow management system or the transaction logs of an enterprise resource planning system can be used to discover models describing processes,

organizations, and products.

Disc over your processes.

Business process management (BPM) is usually a top-down approach. You start by designing your process in a high-level model.

Then, you configure a system for managing and controlling your process.

This system then coordinates work between your employees, and other resources in your organization.

The process discovery has its value in the for humans not visible events and actions being flow:

Process mining can analyze your process in a bottom-up fashion. You don't need to have a model of your process to analyze it ? Process mining uses the history data in your IT systems.

Your IT system already records all steps of your process in execution. With process mining, you get a process model from these data. This way, your real process, and actual business rules, can be discovered automatically.

Big data - Analyzing events

💣 Analysing processes is requiring data. In information processes the number of available events is usually much bigger (volume), generating often (velocity) even chaning quick as of used tools (varicity).

Not every system techniacal system environmment is suited to do this kind of work. Wiht guided sampling the size can get decreased.

This kind of analysis seems to be a fit in a shop floor review, not for continous monitoring.

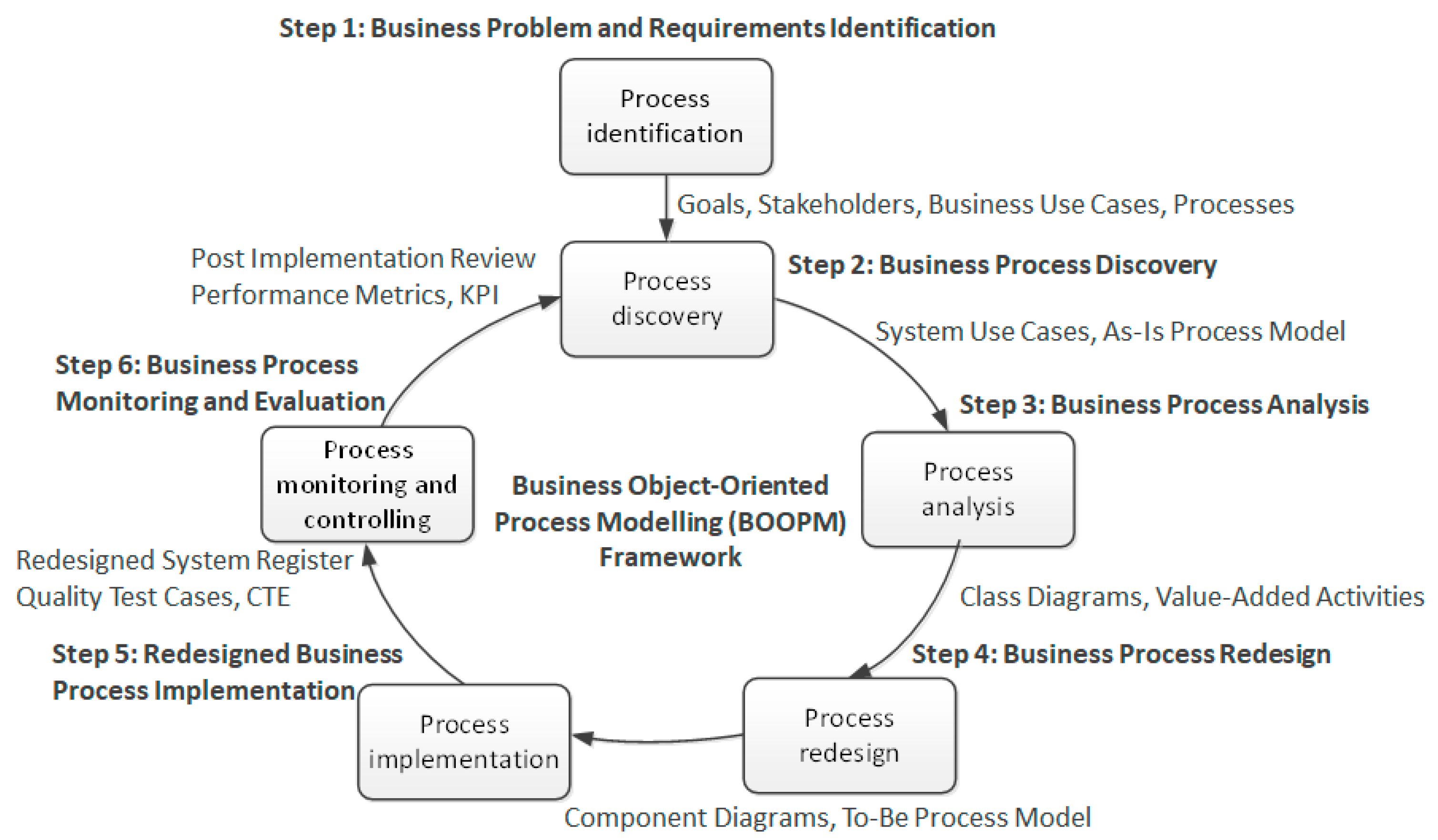

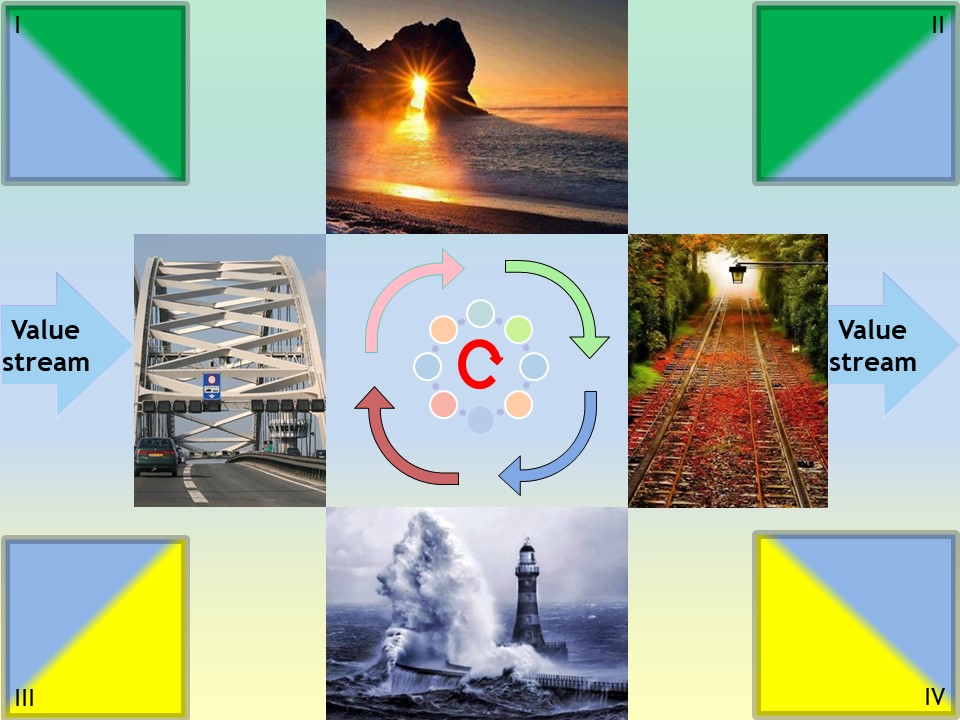

Elementary process cycle..

As long there is a relevant process, that process should continously reviewed and in time improved or abandoned when there are changes. The world is changing continously.

Process cycles at ICT

There are many process cycles at ICT. A generic one is at the SDLC chapter. That one is not technical oriented but focus on the business goals.

Practical example using the process cycle

Improving a business process is a cycle. Adding the vlaue stream concepts is more focussing on business goals.

(Link - reference is at the figure)

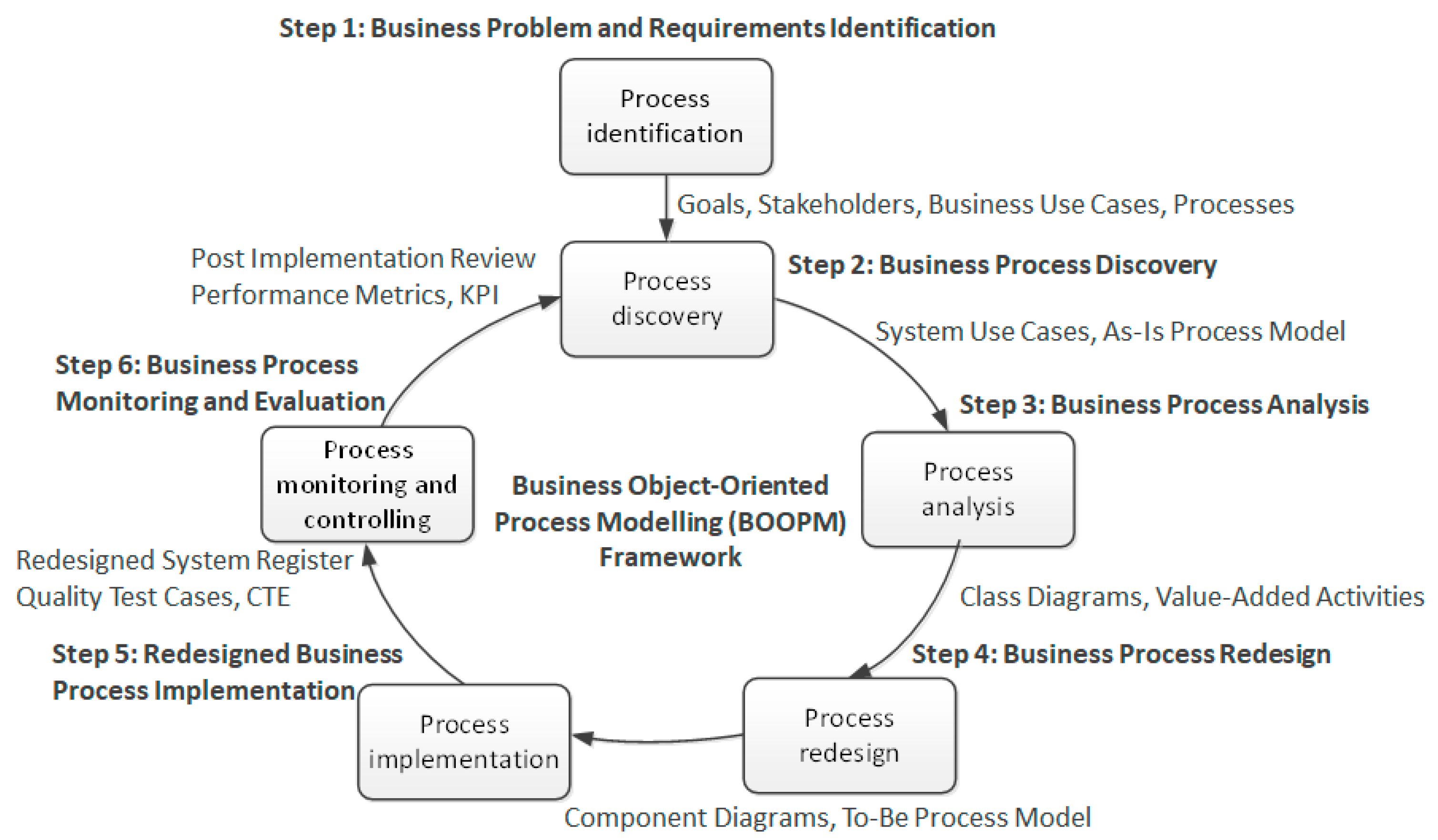

In today´s digital context, business process is considered to be the composition of di�erent activities involving informationization technologies (IT) and people working together

to achieve an organizational goal. Organisations are rigorously redesigning business processes using several best practices with the aim of improving their operations in terms of time, quality, cost, and flexibility [4].

The typical BOOM steps followed by a business analyst in the software development life cycle (SDLC) of an enterprise system are as follows:

- Step 1: initiation: a business case is made for the software project;

- Step 2: discovery: eliciting, analysis, and documentation of detailed requirements are done.Testing activities also occur during this step;

- Step 3: construction: the software solution is built and if an iterative lifecycle approach is being used on the project, requirements, elicitation, analysis, and documentation continue;

- Step 4: final verification and validation (V&V): the business analyst supports final testing before the completed solution is deployed, reviewing test plans and results and ensuring that all requirements are tested;

- Step 5: closeout: the business analyst supports the deployment process, reviewing transition plans and participating in a post-implementation review (PIR) to evaluate the success of change management.

Improving the helpdesk proces using tickets as a service provider applying value stream.

Not only defining there is a proces according to ITIL, The proces can be oursoured, but reviewing that with value on activities.

Inventing change Operations.

There are different views in a process. One is focussing on the processing activities another is focussing on the product, sub products with qualities.

They are strong related, processes are changing products (input) into a new different products (output).

Adding value

💣 Analysing processes is requiring data. There is no real overhead created when the data already present in the main proces can be used.

Adding overhead only by generating the data needed should be evaluated by its adding valued component.

Only adding overhead with the goal of satisfying managers delivering them nice reports, is too often not sensible.

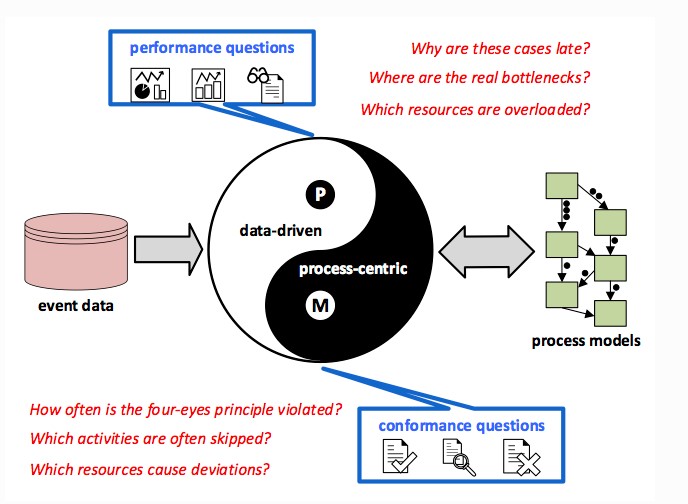

Two powers data and processes

From the same process mining source as previous.

( wil van der aalst)

Questions on processes can be found in data

Processes are delivering data (events)

Combined pages as single topic.

🕶 data info types different types of data

✅ info types different types of information

👓 Value Stream of the inforamtion product

👓 transform information Working cell

👓 bi tech Business Intelligence, Analytics

🔰 Most logical

back reference.

AL-2 Details systems ZARF internals 6x6 reference framework

AL-2.1

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

⟲ AL-2.2.1 Info

butics

AL-2.2

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

⟲ AL-2.3.1 Info

The goal and the flow stability

These are more advanced and tailored to complex organizational and ICT systems, but they still follow the same principle: structured progression through stages of

- Kotter's 8 Steps - Not an acronym, but a staged model - Organizational change management

- 5D Model - Discover Define Design Develop Deploy = Design thinking and innovation

- IDEAL - Initiating Diagnosing Establishing Acting Learning - SEI , ,

- A3 Thinking (Toyota) - Lean problem-solving and reporting

From SEI (software engineering institute)

Barriers to see:

- Initiating

Critical groundwork is completed during the initiating phase.

The business reasons for undertaking the effort are clearly articulated.

The effort's contributions to business goals and objectives are identified, as are its relationships with the organization's other work.

The support of critical managers is secured, and resources are allocated on an order-of-magnitude basis. Finally, an infrastructure for managing implementation details is put in place.

- Stimulus for change It is important to recognize the business reasons for changing an organization's practices.

The stimulus for change could be unanticipated events or circumstances, an edict from someone higher up in the organization, or the information gained from benchmarking activities as part of a continuous improvement approach.

- Set Context Once the reasons for initiating change have been clearly identified, the organization's management can set the context for the work that will be done.

"Setting context" means being very clear about where this effort fits within the organization's business strategy.

- Build Sponsorship Effective sponsorship is one of the most important factors for improvement efforts.

It is necessary to maintain sponsorship levels throughout an improvement effort, but because of the uncertainty and chaos facing the organization in the beginning of the effort, it is especially important to build critical management support early in the process.

- Charter Infrastructure Once the reason for the change and the context are understood and key sponsors are committed to the effort, the organization must set up a mechanism for managing the implementation details for the effort.

The infrastructure may be temporary or permanent, and its size and complexity may vary substantially depending on the nature of the improvement.

- Diagnosing Builds upon the initiating phase to develop a more complete understanding of the improvement work.

During the diagnosing phase two characterizations of the organization are developed: the current state of the organization and the desired future state.

- Characterize Current and Desired States Characterizing the current and desired states is similar to identifying the origin and destination of a journey.

Characterizing these two states can be done more easily using a reference standard such as the CMM for Software.

Where such a standard is not available, a good starting point is the factors identified as part of the "stimulus for change" activity

- Develop Recommendations The recommendations that are developed as a part of this activity suggest a way of proceeding in subsequent activities.

The diagnosing phase activities are most often performed by a team with experience and expertise relevant to the task at hand.

- Establishing The purpose of the establishing phase is to develop a detailed work plan.

Priorities are set that reflect the recommendations made during the diagnosing phase as well as the organization's broader operations and the constraints of its operating environment.

- Set Priorities The first activity of this phase is to set priorities for the change effort.

These priorities must take many factors into account: resources are limited, dependencies exist between recommended activities, external factors may intervene, and the organization's more global priorities must be honored.

- Plan Actions With the approach defined, a detailed implementation plan can be developed.

This plan includes schedule, tasks, milestones, decision points, resources, responsibilities, measurement, tracking mechanisms, risks and mitigation strategies, and any other elements required by the organization.

- Acting

- Create Solution The acting phase begins with bringing all available key elements together to create a "best guess" solution to address the previously identified organizational needs.

These key elements might include existing tools, processes, knowledge, and skills, as well as new knowledge, information, and outside help.

- Pilot/Test Solution Once a solution has been created, it must be tested, as best guess solutions rarely work exactly as planned.

This is often accomplished through a pilot test, but other means may be used.

- Refine Solution Once the paper solution has been tested, it should be modified to reflect the knowledge, experience, and lessons that were gained from the test.

Several iterations of the test-refine process may be necessary to reach a satisfactory solution. A solution should be workable before it is implemented, but waiting for a "perfect" solution may unnecessarily delay the implementation

- Implement Solution Once the solution is workable, it can be implemented throughout the organization.

Various roll-out approaches may be used for implementation, including top-down (starting at the highest level of the organization and working down) and just-in-time (implementing project-by-project at an appropriate time in its life cycle).

No one roll-out approach is universally better than another; the approach should be chosen based on the nature of the improvement and organizational circumstances.

- Learning The learning phase completes the improvement cycle. One of the goals of the IDEAL Model is to continuously improve the ability to implement change.

- Analyze and Validate This activity answers several questions: In what ways did the effort accomplish its intended purpose?

What worked well? What could be done more effectively or efficiently?

- Propose Future Actions During this activity, recommendations based on analysis and validation are developed and documented.

Proposals for improving future change implementations are provided to appropriate levels of management for consideration.

Barriers to see:

- Initiating

- Management assumes that the technology is an appropriate fit for their scheduling problems.

- Diagnosing

- There are no clear criteria for selecting the "best" tool.

- There is no reference model, map, or benchmark selected to support transition.

- There is no clear understanding of current vs. desired states.

- There is no investigation of users' needs.

- Establishing

- No risk analysis is conducted to identify what they didn't know, including potential inhibitors.

- The approach had only one implementation/transition path.

- Acting

- The consequences of risks and barriers listed above surface in the acting phase.

- The software is 2 months late; it couldn't meet user demand.

- Employees were not trained in a timely manner.

- Sarah discovered the MailX problem.

- Sarah discovered the message center problems.

- Learning

- Lessons learned were not tracked

AL-2.3

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

⟲ AL-2.3.1 Info

Core Dimensions of Strategic Thinking

Strategic thinking must be embedded at every level of the organisation, not confined to the C-suite. This requires structured yet flexible processes that promote:

- What ➡Strategic Development Organisations must start with a clear mission and vision, conduct robust internal and external analysis, and define strategic shifts that reflect changing realities.

- How ➡Strategic Translation High-level thinking must be translated into actionable strategies.

Tools such as strategy maps and Balanced Scorecards help articulate cause-and-effect relationships and align teams around common goals.

- Where ➡Organisational Alignment Strategic coherence across business units is essential.

Each team must understand its role in the broader strategy and be empowered to adapt that strategy to its specific context.

- Who ➡Operational Planning Daily operations should reflect strategic priorities.

Leaders must ensure that budgets, initiatives, and KPIs are aligned with long-term objectives, not just short-term performance targets.

- When ➡Monitoring and Learning Strategy should be treated as a living process. Organisations must build feedback loops, review performance data, and be prepared to adjust their approach based on new information or shifts in the environment.

- Which ➡Strategic Agility In an era of rapid change, agility is key. Strategic thinking equips organisations to anticipate multiple futures and adjust course when necessary. Practices like contingency planning and strategic foresight enable resilience.

The why of Strategic Thinking

Strategic Thinking vs. Strategic Planning

While the two concepts are often used interchangeably, they are fundamentally different.

- Strategic planning focuses on implementation, developing roadmaps, timelines, and action plans.

- Strategic thinking focuses on insight, challenging assumptions, identifying leverage points, and choosing where and how to compete.

Planning tends to be linear and predictable.

Strategic thinking embraces complexity and uncertainty.

One is about execution; the other is about advantage.

"Having a good strategy with no execution is a big disappointment.

But having no strategic thinking at all is a failure in leadership."

Flow in of Strategic Thinking

strategic-thinking (Andre Constable 2025)

Strategic thinking is the cornerstone of effective leadership, sound decision-making, and long-term organisational success.

It goes beyond the confines of traditional planning, enabling leaders to make integrated, courageous choices in the face of uncertainty.

In today's complex and fast-changing world, the ability to think strategically has become essential for survival and sustained performance.

- Future Orientation Strategic thinkers do not merely solve today's problems, they look ahead.

They explore emerging trends, anticipate disruptions, and use structured tools such as scenario planning, PESTLE analysis, and competitive landscape assessments to guide long-term decisions.

- Systems ThinkingOrganisations are part of broader ecosystems.

Strategic thinkers recognise interdependencies across functions, partners, industries, and geographies.

This holistic view is crucial for addressing systemic challenges and capitalising on cross-sector opportunities.

- Hypothesis-Driven Strategy Effective strategies are built on assumptions.

Strategic thinkers make these assumptions explicit and test them rigorously.

Whether through war-gaming, pilot projects, or feedback loops, they continuously refine their approach based on evidence.

- Clarity and FocusClarity in purpose, values, and direction is a hallmark of strategic thinking.

These elements act as guardrails, shaping what the organisation will and will not do. Organisations that define their identity clearly are more likely to make coherent, disciplined choices.

AL-2.4

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

⟲ AL-2.4.1 Info

butics

AL-2.5

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

⟲ AL-2.5.1 Info

The goal and knowledge stability

On this site references to frameworks like Jabes, JABSA, and SIMF, which extend traditional cycles with deeper abstraction layers.

These integrate:

- CES: Strategic, Tactical, Operational enterprise processes

- CPI: Controlled innovation and change

- CTO: Technology build, run; devops cycle

- 6*6 Reference Framework: A multidimensional matrix for systems thinking, combining perspectives like What, Why, How, When, Where, Which across internal and external flows

These are more advanced and tailored to complex organizational and ICT systems, but they still follow the same principle: structured progression through stages of

- understanding,

- planning,

- acting, and

- refining.

AL-2.6

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

⟲ AL-2.6.1 Info

What are Frameworks?

Value Requirements (T.Gilb 2025)

Value Requirements are the most important requirements for any project.

They are the main purpose, and main justification, for a project.

They are the stakeholder's values.

Value requirements start life as value "attributes", needed by stakeholders.

No project can deliver all needed values, by a deadline.

No project will find all stakeholder values to be worth delivering.

So all value requirements start life by being acknowledged as possible delivery candidates.

But VRs need to go through an evaluation process to determine that we can prioritize them for real delivery.

reflections on how lean really works

Value Requirements (T.Gilb 2025)

Because lean thinking is a study of challenges and responses, it's really a study of how we define challenges together and how we build responses together, according to each person's unique perspective, interests and special insights. To a large extent, lean thinking is not just a science of improvement, but also a science of building stronger teams.

Lean is not for everyone. Not because it's particularly mysterious or complicated, but because it requires four deep commitments: to face our challenges in order to find more value to deliver; to be disciplined in our responses, both with routine problems and new, unexpected ones; to self-train and learn what we have to learn in order to succeed at responding to our challenges (which, in lean, men ans accepting to follow a sensei where and when he or she points the way); and to do it all together.

It's easy to mistake the lean system for a toolbox: apply this tool to this problem and things will automatically improve. It's equally easy to fall into the opposite extreme and think that coaching doesn't require the constraints of the TPS (or cherry-picking your favorite aspect of the system as the only you need hint: it's a system!). In truth, the system is a concrete, hands-on theory of improvement that helps the sensei to find which exercise will make you progress right now (just as the sensei will progress in his or her understanding of the system itself).

Lean is a self-development method, not an organizational framework. And yes, we all have good days and bad days.

Sometimes we think the work is good enough (why can't customers see how hard I work and how difficult it is, for a change?).

Sometimes we're under pressure to cut corners, and then to cover up cutting corners. Sometimes, we simply can't be bothered to challenge habits.

And that's ok. The point of a lean system is that it remains there for us when we want to get back on the bike and keep climbing up the learning curve, no matter how often we fall. The deeper learning is always right behind the lesson we currently struggle with. Which is also what makes it endlessly fun.

AL-3 Details systems ZARF externals 6x6 reference framework

AL-3.1

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

⟲ AL-3.1.1 Info

butics

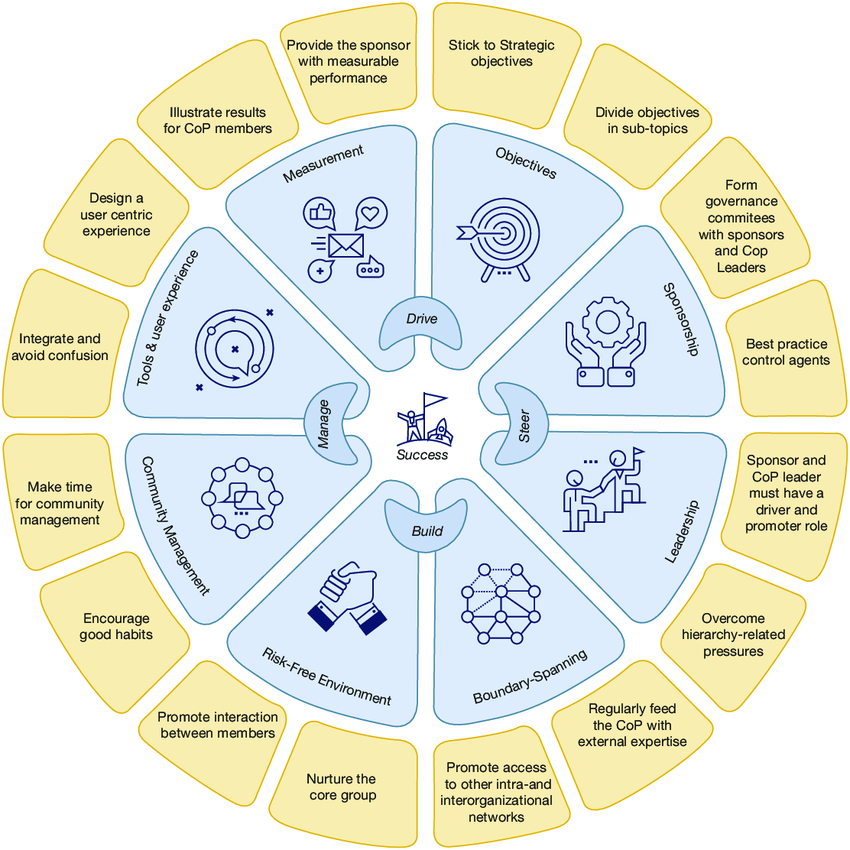

A case study for organizing the organizing is a source for good example for using Zarf and Jabes.

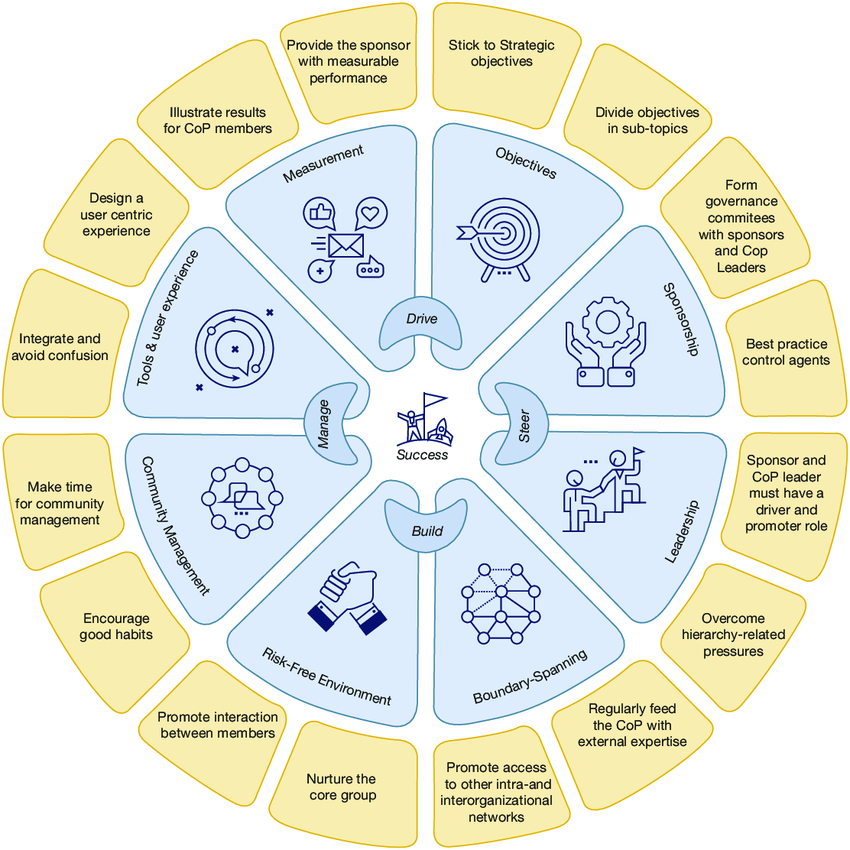

Although nowhere Zachman is mentioned there is a remarkable similarity by the 4 disciples Steer Build Manage Drive in 6 levels.

It is case study by observing what and how it is done, there is no attempt to align that to any scientific theory.

Science for Policy Handbook (EU JRC july 2020).

Communities of Practice Playbook CoP (EU JRC july 2020)

that is associated with a short (100 pages) handbook

Science Communities of Practice Playbook light (EU JRC july 2020)

In a figure:

see right side.

Scientists and policymakers need to work closer together to deliver progress for our societies, economies and our planet.

For the last 60 years, the Joint Research Centre (JRC) has been working at this interface for the European Union.

This handbook collects what we have learnt about the science–policy environment and shares our vision, best practice and innovative ideas to deliver impact for our societies.

The fact that we are an organisation working not only in a policy context but also inside a policymaking institution is an important lens through which the advice in this book has to be interpreted.

We support policymaking at all stages of the policy cycle and often in direct collaboration with policy departments.

While we take a policy-neutral stance, our mandate is to produce science relevant for policy and generating insights needed to create policy options.

Policymaking is a complex process that includes both an analytical and a normative dimension.

This leads to a twofold problem. On the one hand, scientists and policymakers will define problems differently: one as something to solve technically, the other as a much more social process of negotiating solutions that have majority support.

Therefore, their thinking and problem-solving strategies will be different, given that policymakers need to find the best knowledge and make sure it leads to a consensus or at least a majority on values, i.e., is both technically and politically feasible.

butics

It is case study by observing what and how it is done, there is no attempt to align that to any scientific theory.

Science for Policy Handbook (EU JRC july 2020).

The isues:

Chapter 1 page .

Chapter 2 page 18 PNS Post Normal Science.

In the social process of science, quality is achieved, not by a delusory pursuit of certainty, but by the skilled management of its uncertainties, involving all who have a concern for the issue.

Cocreation

Chapter 3 page 22 lighthouse

In the past, knowledge was produced by universities, mainly in North America and parts of Europe.

At the same time, the old, trusted, established knowledge outlets have lost or risk losing at least part of their authority.

Just as in the media landscape, the old reference points are dissolving. ...

Unlike the scientific method, which is based on the formation of hypotheses, these methods are inductive, based on picking out patterns and correlations in the data.

Much of this work may not be reproducible, as the scientific method requires, because the data on which it is based are constantly evolving.

... The border line should not be made between "scientific" and "nonscientific" knowledge but between false and real facts.

If science was able to embrace a role of a verifier of quality of arguments, it would strengthen its legitimacy to hold a privileged position in the policymaking process.

Chapter 3 page 24

Due to the growing complexity and importance of decisions, it seems to be wiser to put in place advisory groups or structures, where the constant interactions between scientists and policymakers are allowed. ...

one type of organisation has a particularly important role to play, that is, "boundary organisations", i.e., those which sit at the intersection of science or knowledge and policy. ...

‘Wicked challenges’ rarely have definitive solutions, so scientists and policymakers have to stay in constant and ongoing dialogue with one another.

This constant interaction is a key to mutual understanding, building trust and overcoming of the differences between scientific and policymaking cycles.

Chapter 3 page 26

Managing the existing knowledge, verifying it and making sense for different purposes should become an additional dimension of every knowledge organisation. ...

Making sense of knowledge is a challenge for the whole society.

If almost all players are now producing large amounts of data and knowledge, they are also all struggling to cope with the deluge that is being created.

Chapter 4 page 41 Skills co-creation

In recommending eight skills, we argue that "?pure scientists" and "?professional politicians" cannot do this job alone.

Scientists need "?knowledge brokers" and science advisors with the skills to increase policymakers' demand for evidence.

Policymakers need help to understand and explain the evidence and its implications.

Brokers are essential: scientists with a feel for policy and policymakers understanding how to manage science and scientists.

Chapter 5 page 51 Achieving policy impact

Timing is a crucial driver of policymaking. Being on time and respecting the deadlines is key if one wants to receive any place in the policymaking process.

However, figuring out the right timing and the expectations is not always easy or in control of the scientists.

When policymakers are under time pressure to gather evidence, the strength of the existing relationship plays a role in whether scientists will have a window of opportunity.

Chapter 6 page 53 Co-creation (suggestions - ideas)

Instead of attempting to "translate" research results at the end of a project, systemic cocreation of research questions early in the process helps mitigate that problem.

... Using cocreation in deciding what to study brings two main advantages.

It improves the relevance of the science, both through microlevel discussions on specific questions and macrolevel strategic planning of broader research topics.

... Exchanging only dry assignments and working in isolation without a proper debate on what to study will not help either side achieve their goals.

Chapter 6 page 56

It is also impossible to objectively verify whether the solution to them is "true" or "false", as in the case of science (where a hypothesis can be objectively verified).

Defining a problem dictates the realm of solutions, and as such is a nonneutral exercise.

Moreover, there are no criteria that enable one to prove that all solutions to a wicked problem have been identified and considered (p. 164), which makes the process imperfect by nature.

... Policymakers still need to answer the analytical parts ? to figure out what the technical possibilities to reach an objective are ? but they simultaneously need to reconcile conflicting values and objectives and also ensure that the course of action is approved by a majority, including of the public.

... Framing a policy problem is a political decision and an expression of power.

However, it is not always a fully conscious choice.

Particular definitions of a problem can seem obvious due to unconscious cognitive shortcuts, such as availability bias, confirmation bias and group reinforcement, among others (Hallsworth et al., 2018).

... Sometimes it means that the questions initially posed change radically because only through dialogue both sides realise the true extent of the knowledge gaps and evidence needed to bridge them.

As policy questions and research questions are not interchangeable, there is a need for an iterative process of translation from policy questions to research questions.

This implies active engagement, openness and attention to detail. It has to be done in a cocreative way, including opening up and ?questioning the question?.

Chapter 6 page 56 (scope limiting top-down)

In the JRC, this approach is complemented by a top-down process, the Work Programme.

Designed to provide an overview of the JRC?s annual research activity, its coordination process provides additional benefits.

Indeed, the Work Programme goes through a set of formal processes throughout its yearly production cycle, which allows policy considerations to input into research planning.

For instance, the Work Programme undergoes ex ante and ex post evaluations, whereby independent panels scrutinise respectively planned work and delivered outcome to check their policy relevance.

At the ex ante stage, panels deliver opinions to senior staff on such relevance. These opinions trigger strategic discussion at the top level of the organisation and can lead to significant modifications.

Chapter 6 page 62 (other stakeholders)

Done well, through an interaction and with the inclusion of citizens? and stakeholders? perspectives, these processes bring an increase in quality of science for policy in a complex world.

A broader consensus, as opposed to singular decision of either scientists or policymakers, increases the legitimacy and relevance of the knowledge being produced.

Chapter 7 page 63 the wheel

Offers a self-assessment tool for a community ? the CoP Success Wheel ? encompassing eight success factors.

For a community to succeed, it is important to create the right environment which includes setting strategic goals and objectives, real governance and support from senior management,

empowered community leaders, investment in the community management role and sound and user-friendly digital environments to host conversations, exchanges and repositories of knowledge.

To tap into a crowd?s wisdom and avoid tapping into a crowd?s madness (Bonabeau, 2009), it is important to get the mechanisms for harnessing the power of collective intelligence right.

When the MIT Centre for Collective Intelligence looked into hundreds of examples of webenabled collective intelligence, researchers identified a small set of building blocks as the ?genes? of collective intelligence systems (see Fig. 1).

Two dualties what / How-where and who-when / why.

Goal 1: Ensure coherent and coordinated mapping activities across JRC and EC 4 behaviours.

Behaviour 1 When working on a new map, members consult the CoP reference space to check for geographical correctness, mapping conventions and links to key resources (e.g., GISCO, ESTAT, etc.).

Behaviour 2 Members share/point to their maps in the community.

Behaviour 3 Facilitator creates reference library in the community, which covers geographical correctness, mapping conventions and links to key resources.

Behaviour 4 Geographic information system users from policy departments join the community

Goal 2: Improved efficiency and effectiveness of mapping 4 behaviours.

Behaviour 1 Members post their questions and challenges.Facilitator responds to questions on geographical correctness by pointing to key resources and by inviting other members to respond.

Behaviour 2 Members inform peers about their upcoming mapping activities and projects.

Behaviour 3 Members attend regular face-to-face meetings to discuss topics of their interest.

Behaviour 4 Members identify shared training needs.

Chapter 7 page 73 digital tools

Digital tools hosting CoPs do not need to be complex, normally requiring functions such as forum, document libraries, expertise finder, teleconferencing and ideally video conferencing and online places where members can edit documents and discuss them.

For example, the European Commission uses SharePoint, Yammer and Jive software for hosting internal CoPs and Confluence, Wikis and Drupal for CoPs involving members from outside the organisation.

One can check some communities run with external partners on the JRC's Science Hub.

No dedciated tool metatdata oreiented for supporting the knowledge.

Chapter 7 page 73 figure 4

Four parties: Researchers (creating) , Community management (administration), Adivisory policy makers (processes), Decision making policy makers (strcuture)

Chapter 8 page 84 citizen engagement.

Four activities: Adaption, Implementation, Application, Preparation and Outcomes, Methodology, Context, participants

There is a great deal of citizen engagement already out there, organised by other institutions and organisations, such as academia and NGOs but also grassroots initiatives in the form of activism, ?community? action, making and hacking.

Chapter 8 page 86 citizen engagement.

Identifying Who Should Be Involved Who are the citizens? Those concerned, the ?getroffen? (sufferers), stakeholders, voiceless and disempowered, community members?

Chapter 9 page 99 (information age - Me:disappointing assumptions expectations)

The interest in AI is rather recent even if the underlying methods date back to the 1950s.

This new found interest in AI, and ML in particular, results from the convergence of three developments:

(i) increased access to cheap computing storage and processing capabilities,

(ii) increased availability of big data on which to train algorithms and address previously hard problems such as object recognition from digital images and machine translation and

(iii) improved algorithms and increased access to specialised open source ML software libraries that make the creation and testing of ML algorithms easier.

Chapter 10 page 106 (the risk in trustworthiness)

Nothing justifies playing with data to fit any particular interest in the policymaking ecosystem.

It can happen that scientists may feel the need to artificially fit the scientific facts to policy agendas, to preserve a long-established relationship, gain new influence areas, and secure more impact or funding.

The pressure can even directly come from policymakers. This is both ethically inadmissible and diminishes scientists? credibility given that policies and their background science are scrutinised by other actors and observers in the process.

There is a growing understanding that facts are established through a social, culturally-dependent process.

Disrespecting the distinction between advocating for scientific evidence and promoting oneself and one's convictions damages the trust people have in reputable scientific expertise.

With many different stakeholders in the field, scientists and their organisations should learn a little bit about the main issues, opinions and constraints of each group in order to be able to identify them but also to better understand their positions and possibly benefit from their insights.

Backbone tools

Chapter 11 page 119 Systems thinking

It is necessary to change the perspective from the parts of the system to the connections between the parts and to the system as a whole, i.e., from reductionism to holism.

Reductionism and holism are complementary. Many real-world systems show nonlinear interactions and are rarely in equilibrium.

They show phenomena such as

adaptation (e.g., markets, innovation),

the formation of hierarchies (e.g., public and private organisations, discussions),

self-organisation (e.g., collective decisions, public opinion formation),

robustness and fault tolerance (e.g., many biological systems),

resilience (e.g., ecosystems, some technological ?ecosystems?),

lack of central control (e.g., collective decisions in social insects, bird flocks, fish swarms, task allocation in computer systems) and other features well known from complexity science (CS).

None of theseproperties can be understood on the basis of the properties of the parts of the system alone.

Chapter 12 page 130 insight to foresight (predictive prescriptive)

Foresight helps creating anticipatory governance capacity and awareness about future-related issues.

It enables policymakers to make prudent long-term decisions, helps revealing the need for policy action and channel evidence into policy discussions.

A question then arises about how to be authoritative when acting to shape a future that does not exist yet.

This is why public policy should take into account consciously a future time dimension even if its focus is on immediate public concerns. ...

Even if, by nature, VUCA elements are unpredictable, a well-prepared and resourced foresight approach can provide surprising levels of understanding about what could happen and how to deal with it (Da Costa et al., 2008).

Short-sightedness, narrow-mindedness, simplistic lines of thought, linear thinking and lack of understanding of the past are probably the worst enemies of policymakers in a VUCA world. ...

While evidence is available for past and present developments (statistical data, scientific reports, etc.), there is no such thing as facts about the future as the future does not exist.

The challenge is therefore to generate meaningful (and useful) knowledge about the future by interpreting facts about current developments and use imagination about the future (Duvka, 2020; EFFLA, no year). ...

Chapter 13 page 146 introducing design thinking byt simi to systems thinnking

Design-based approaches are systemic in nature, explore complex context using visual methods, bring several disciplines together to make sense of the problem space and formulate proposals that focus on the quality of the experience from the point of view of the final beneficiaries. ...

The word ‘design’ has accumulated several different uses and its meanings shift according to the context in which it is used. ...

Chapter 14 page 153 measuring monitoring the policy process suffering in prejudice and pride

When a research organisation covers a wide range of topics and policy areas, capturing the impact of its activities presents a methodological challenge due to the multitude of different impact pathways which are not always easily traceable.

In our experience, this can be overcome by employing a range of tools to measure impact, starting with documenting impact pathways, building impact inventories and case studies and performing portfolio analyses. ...

Public research organisations need to demonstrate the impact of their research on policymaking or the society, and thus the value of public investment in research. ...

Finally, the inventory can be used to select related activities and impacts and analyse the portfolio in a given research or policy area.

The feedback loop is closed when portfolio analyses discover gaps to be addressed by analysing new case studies of an organisation’s research activity. ...

It is thus paramount to imagine the possible effects of one’s research on how policy is designed, implemented or evaluated, as this provides accountability for the public funds spent on research. ...

"better" science portfolios […] would be achieved if science policy decisions reflected knowledge about the supply of science, the demand for science, and the relationship between the two’.

Chapter 15 page 168 to a Broader Audience (the nitwits)

Often these audiences, especially citizens, can only be reached indirectly, via multipliers like the media or social media influencers.

Furthermore, the co-creation and continuous engagement approach that Science for Policy 2.0 calls for with policymakers is only possible to a lesser extent with broader audiences as those approaches rarely scale to the level needed to reach them, and even if they do, they can be very resource intensive and thus out of reach for most organisations.

Communication activities will thus vary according to the objective, the intended audience and the resources available.

Specific areas:

Chapter 16 page 183 Knowledge-Based Crisis and Emergency Management.

A golden rule in crisis and emergency management is to handle crises as local as possible and as global as necessary ..

The most important lesson is that scientists, policymakers and practitioners must work together. ...

Scientists must learn what information to provide to whom at what time and in what format, so the information is directly relevant in the decision-making process of practitioners. ...

The Copernicus Emergency Mapping Rapid Mapping Service (http://emergency.copernicus.eu/mapping/) is the operational outcome of years of research at JRC. ...

Chapter 17 page 197 Behavioural Insights

Behavioural insights are evidence-based conclusions about human behaviour in a given context.

The behavioural sciences are all those disciplines that, through systematic observation and rigorous analysis, offer these insights. ...

The best starting point for appreciating the contribution of behavioural insights is the assumption, explicit in economics and implicit in much of policy thinking, that human beings are rational.

They maximise their well-being, or utility in the economics nomenclature, taking a number of variables into account and following a series of axioms.

The assumption of rationality refers mainly to the outcome of decisions, not the process (i.e., a decision is considered rational if it maximises utility, regardless of how that decision was arrived at).

Circumspect analysts might take this assumption with a grain of salt but will nevertheless adhere to it. It is useful for economic analysis.

However, as we know intuitively from observing our own behaviour and that of others, humans are far from rational.

We exhibit consistent anomalies in our behaviour, oddities that cannot be properly explained by the assumption of rationality.

These biases and heuristics have been identified through experimental studies and form the basis of behavioural economics (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979). ...

Chapter 17 page 199

People exhibit two ways of thinking. One (System 1) is characterised by being automatic, unconscious and frequent.

It is prey to cognitive biases and strikingly prevalent in our everyday lives, accounting for about 95% of our thinking according to some estimates (Zaltman, 2003). ...

Why does the distinction between System 1 and System 2 matter and how is it relevant to policymaking?

Because the design of many a policy initiative is based on the assumption that citizens routinely use System 2, whereas in fact, they may be using System 1. ...

Chapter 17 page 203

Moreover, there is the problem of diversity. Unlike national or regional policies, EU policies have to be effective in 28 different member states.

And results from RCTs are not necessarily transferable to other contexts (Cartwright, 2007). Interventions that work in Denmark might easily fail in Italy. ...

Apart from experiments, qualitative methods have also proven useful.

These include in-depth interviews, focus groups and participant observation, among others. They are different to experiments in their approach and fulfil a different purpose.

For one, they do not seek to test hypotheses, but rather generate them.

Their findings are not ‘objective’ (i.e., the perspective of the researcher must always be taken into account) or statistically generalisable. ...

Uncovering meaning is important, but not easy. It requires a rigorous, reflective and systematic process. Good qualitative evidence is not anecdotal. ...

Chapter 18 page 207 Quantitative Methods in the Policy Cycle

for any policy modelling exercise, there is a need to decide what is important for different social actors as well as what is relevant for the representation of the real-world entity described in the model (see, e.g., Frame and O’Connor, 2011; Jerrim and de Vries, 2017). ...

However, theoretical models have their limits and can never fully capture reality in all of its complexity.

Ultimately, policymaking is bounded by a reality check expressed by the simple question: what worked and for whom? ...

For example, in the European Commission, more than 200 models are applied within various policy departments and services with hundreds of scientific and administrative users in various countries.

The list of domains ranges from greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, energy consumption and economy to structural integrity assessment, to name but a few. ...

In order to address some of these challenges, the corporate modelling inventory and knowledge management system, MIDAS contains descriptions of models previously or currently in use in support of the EU policy cycle (Ostlaender et al., 2015).

Chapter 19 page

The systems thinking triad (Graham Berrisford 2024)

A confusing mix of: work system theory (WST), domain-specific systems theory (DSST) and general systems theory (GST).

In pursuit of systems theories for describing and analyzing systems in organizations (Twenty-Sixth European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS2018), Alter, Steven 2018)

The visibility and application of systems theories in the IS discipline have not come close to achieving the promise implied by the name of discipline. ...

The treatment or omission of systems theories in recent articles about perspectives or approaches in IS research provided an additional impetus to discuss systems theories in a more direct and specific manner. Burton-Jones et al. (2015) compares variance, process, and systems perspectives in IS research, each of which represents “a researcher’s choice of the types of concepts and relationships used to construct a theory.”

It notes that papers comparing theoretical perspectives tend to “emphasize the variance/process dichotomy without mentioning the systems perspective.”

It describes an unproductive tendency to keep the different perspectives separate and proposes ways to combine aspects of variance, process, and systems approaches. ...

GST purports to be a transdisciplinary theory that identifies properties shared by all systems (see above).

The next two use the term system as a rough synonym for a tool that is adopted or liked.

Soft systems theory is really an alternative name for soft systems methodology, less a theory and more a system-oriented method for problem identification and problem solving.

WST will serve as this paper’s primary example for illustrating the potential of systems theories in IS.

The IS Theories Wiki did not include several widely used systems theories that that will be mentioned later, i.e., activity theory, sociotechnical systems theory, and the viable systems model.

The Illusion of Resilience

Leadership at the Edge of Chaos for safety (D.Nichols DVMS 2025)

Executives and board members often assume their organizations are resilient because they’ve invested in the right technologies, hired skilled staff, or achieved compliance certifications.

Yet every crisis tells us the same story: what fails first is not the firewall, the supply chain contract, or the policy binder: it’s leadership.

Hidden in plain sight, leadership gaps are revealed when stress hits the system. Failed digital transformations, high-profile breaches, and supply chain shocks aren’t stories of technical incompetence.

They are stories of intent that weren’t matched with structure, culture that betrayed stated values, and boards that assumed when they should have demanded proof.

But ask yourself:

- When was the last time your board demanded evidence — not assurances — that your suppliers could deliver under stress?

- How often do you test whether your organizational structures reflect your strategic intent?

- Do your cultural behaviors under pressure match the values you’ve put on the wall — or do they collapse when a crisis arrives?

If you can’t answer with confidence, your resilience is an illusion.

Representing ideas in visuals orientation distractors.

The practical thinking in thinking

'Crossing the chasm'

model developed by G.A. Moore helps to successfully drive the adoption of the product in the market, across different customer segments.

The most challenging step is making the transition between the chasm of Visionaries and the Pragmatists.

- Tech Enthusiasts (Innovators): They look forward to get the latest technology, and are less concerned with functionality and benefit.

- Visionaries (Early Adopters): Similar to Tech Enthusiasts, the Visionaries group is all about trying out new products.

They have a direct need for the product, and need less of convincing to adopt the new product, if it meets their need.

- Pragmatists (Early Majority): They are open to innovation and embrace changes, however they only buy when the product is proven to provide the said benefit.

They are less tolerant of technical issues than Visionaries. There exists a wide Chasm (gap) between the Visionaries and Pragmatists group of people.

- Conservatives (Late Majority): This group adopts a new product only when they feel a loss by not adopting the product.

Most users in this stage are aware of the product, however, they are hesitant to adopt (and spend money on) something new.

- Skeptics (Laggards): They only buy product when it's forced upon them. They are very resistant to change, risk-averse, and not easily persuaded.

They finally come around once all of the buzz about your product has quieted down.

Technical documentation

The developer is responsible to create the technical documentation of the product from both internal and user perspective.

Internal documentation are prepared over the course of entire development.

User documentation is created at the end of the User Acceptance testing (UAT) and released along with the Product.

butics

Amplio

Factors for effective value streams enable us to accurately predict what practices will work best in our situation.

This segment is part of Amplio Foundations.

Amplio Axiom’s - Why theory is so important.

- Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

- The Importance of systems thinking

- First principles of knowledge work and managing complexity

- Understanding Value Streams.

- Factors for Effective Value Streams

- How Amplio Uses Patterns

Factors for Effective Value Streams

Factors for effective value streams are derived from first principles and enable us to discern how effective our value streams are.

They are based on Eli Goldratt’s theory of inherent simplicity that suggests “If we dive deep enough, we’ll find that there are very few elements at the base – the root causes – which through cause-and-effect connections are governing the whole system.” They are framed as questions to ask and can be used to decide between optional practices.

See Amplio books for more.

- Working on the most valuable items to achieve success for your critical stakeholders.

- Understanding the acceptance criteria before writing any code.

- Getting actionable feedback quickly on your product and on how you are working.

- Working in small increments.

- Using pull to keep workload within capacity.

- Managing work in process at all levels to reduce delays in your workflow.

- Organizing people to avoid multi-tasking and delays in people being available.

- Having clarity on how people work together.

- Making all work visible.

- Focusing on the quality of the product

AL-3.2

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

⟲ AL-3.2.1 Info

butics

VSM metaphore

The VSM outlines five interrelated subsystems necessary for any system (organization, society, organism) to remain viable—able to survive in a changing environment.

| Role | Function | Metaphor |

| system-1 | Operational units | Muscles doing the work |

| system-2 | Coordination | Nervous system—managing tension |

| system-3 | Control & optimization | Liver—resource distribution |

| system-4 | Intelligence/Adaptation | Brain—future planning |

| system-5 | Policy/Identity | Prefrontal cortex—purpose & values |

The Lean Problem

Wanting to have a desired culture and what to do about that is a chaotic problem.

About Culture — and Why Lean Gets It Wrong (K.Kohls 2025)

Too often, Lean is sold as a six-month miracle. Leaders expect a culture shift after a workshop, a kaizen event, or a certification. ...

Culture doesn’t happen in six months. It grows through repetition, feedback, and reward loops, engineered into daily work until they finally stick. And that always takes longer than we expect. ...

The Toyota Production System (TPS) wasn’t built on slogans or mindset speeches. It was built on habits, repeated daily for decades:

- Pull the cord when there’s a problem.

- Level the flow of work by identifying and addressing large inventory piles.

- Improve a little, every day.

Thirty years of these loops compounded into culture. Workers didn’t need a poster telling them to “think Lean.” They simply did the habits, and the culture followed.

TPS didn’t sustain for 30+ years because people believed harder, it sustained because the habits were simple, repeatable, and reinforced every day.

If we want cultures that last, we need to stop selling the six-month miracle. We need to design the loops that trigger dopamine, reinforce oxytocin, build serotonin through progress, and manage cortisol under stress. Habits first. Culture second.

The Change Problem

The Real Reason People Resist Change (And How to Fix It) (K.Kohls 2025)

Peter Senge once said: “People don’t resist change. They resist being changed.”

It’s a deceptively simple insight. Change itself isn’t the problem—most of us welcome progress, better tools, and smarter ways of working. What we resist is having change forced on us without agency, without understanding, and without reinforcement.

Drive Organizational Change Without Top Leadership (K.Kohls 2025)

Variations on: Machines, People, Processes, Structure

Where founders lose leverage - and how to get it back (L.Tobin 2025)

The Four Levers That Hold the Keys.

Every founder has four main levers:

- Structure Capital: Is your money being put to work (through marketing, product, or expansion) rather than sitting idle?

- Processes Time: Are you investing your hours in high-value activities, or stuck in operations?

- People Team: Do you have the right people (or partners) carrying the right responsibilities?

- Machines Tech: Are you automating repetitive tasks and using systems to create scale?

Most founders lean heavily on one pillar and neglect the rest. But scaling happens faster when you optimise across all four. ...

Once you see it this way, it’s obvious why optimising all four levers is non-negotiable.

Cognitive psychology tells us the brain is wired for conservation of effort. We cling to what feels safe (usually time and control) and avoid what feels risky (deploying capital, delegating, automating).

The way out of this trap is to build “disconfirming evidence.”

Consolidations:

most teams are stuck fighting the same fires (A.Singh 2025)

Consolidations:

why-cheap-is-the-most-expensive-decision-activity (Alper Ozel 2025)

AL-3.3

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

⟲ AL-3.3.1 Info

butics

Frictions in the internal purpose line culture

States in the internal purpose line culture for the future

An example for leaders what they should do by practices.

18 practices for ceo's (Alex Nesbitt 2025 reference to McKinsey)

What are the better attitiudes?

- What ➡External Stakeholders Centre on the long term "why" (purpose)

- How ➡Board engagement Help directors, help the business

- Where ➡Team & processes Put dynamics ahead of mechanics

- Who ➡Personal Norms Do what you can do

- When ➡Culture & organisation Manage both health and performance

- Which ➡Corporate strategy Focus on beating the odds.

Positive actions in transformations

18 practices for ceo's (Alex Nesbitt 2025 reference to McKinsey)

- Universe ➡ (What) External Stakeholders

- Commit to making a positive big picture impact

- Prioritize stakeholders and shape their views

- Build capabilities/resilience before the crises

- (What) External Stakeholders ➡ (How) Board engagement

- Promote an agenda beyond the financials

- Build and foster active board relationships

- Transform the board from passive and weak to active and capable

- (How) Board engagement ➡ (Where) Team & processes

- Actively strengthen the team and its teamwork

- Defend against bias (cognitive and social)

- Ensure coherence across processes and levels

- (Where) Team & processes ➡ (Who) Personal Norms

- Seek out high-quality support and advice

- Authentically connect purpose to leadership

- Counter hubris with candid advice and practices

- (Who) Personal Norms ➡ (When) Culture & organisation

- Match high impact roles with best talent

- Actively drive organisation effectiveness

- Decide wat needs stable and what needs to be agile

- (When) Culture & organisation ➡ (Which) Corporate strategy

- Reframe the definition of winning

- Make bold moves early in your tenure

- Actively redistribute resources to strategy

- (Which) Corporate strategy ➡ Universe

- (intentionally left empty)

This is where the Matrix lives. The challenge of the X-matrix is that only the half, three cell items of the complete line of six ordered cells is present.

Negative actions in transformations

18 practices for ceo's (Alex Nesbitt 2025 reference to McKinsey)

- Universe ➡ (What) External Stakeholders Minimize time with external stakeholders

- Focus solely an shareholder value

- Engage in ad-hoc reactive manner

- Assume crisis aren't going to happen

- (What) External Stakeholders ➡ (How) Board engagement Stay hands off:

- Passively let the board control the agenda

- Minimize interactions and avoid the board

- Let the board evolve without a plan

- (How) Board engagement ➡ (Where) Team & processes Avoid responsibility for the team:

- Allow silos, discord and passive aggressive behaviour

- Avoid debate and "final" decisions

- Become a captive of the bureaucratic system

- (Where) Team & processes ➡ (Who) Personal Norms Let the world happen to you:

- Let the system define your schedule and priorities

- Adapt a fixed mindset = I am who I am

- Cultivate a "royalty" like status

- (Who) Personal Norms ➡ (When) Culture & organisation Diplomatic avoid social issues:

- Work around mediocrity and low performance

- Assume desired behaviours and values will be followed

- Put feelings before effectiveness

- (When) Culture & organisation ➡ (Which) Corporate strategy Let a thousand flowers bloom:

- Make vague and generic statements of intent

- Make small bets with unclear paths to scale

- Maintain the status quo

- (Which) Corporate strategy ➡ Universe

- (intentionally left empty)

This is where the Matrix lives. The challenge of the X-matrix is that only the half, three cell items of the complete line of six ordered cells is present.

There is a natural variation over all components by cells and transformations interactions between the cells.

AL-3.4

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

⟲ AL-3.4.1 Info

butics

Intra References

BiAnl, OR, is applicable to almost anything in an environment.

The following is about what was doen before in understanding BiAnl:

Intra References by topics

Shaping a cylce is touching almost anything in an environment.

The following relationships are here in the mindmap approach:

AL-3.5

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

⟲ AL-3.5.1 Info

butics

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/edwinstam1_latenweverbinden-heelheid-teamvanteams-activity-7378937876979351552-y2JB

Ik heb weer eens een uitdager in deze.

Ik zie vier statische waarden in dualiteiten waar kennelijk iets meetbaars achter zit of een meetbaar doel:

- Orde <-> flexibiliteit

- Taak <-> Mens

Afgewisseld met 4 transformerende processen in een zelfde setting:

- gezellig <-> discipline

- innovatief <-> bezieling

Net een centrale aansturing/waarneming kun je hem ook als een cirkel zien. Die is verder uit te bouwen met details.

Ik zoek in deze nog wat het doel is,

- taken naar doel van wat "mens" is

- Vanuit een "mens" naar taken.

Fexibiliteit en order lijken me geen doel maar iets wat helpt bij dat andere

Dank. De goede vragen zijn vaak belangrijker dan de goede antwoorden. Het team in een reflectieve modus brengen :-)

Gartner's Enterprise Architecture (EA) Framework offers a business-outcome-driven, capability-based approach to EA, focusing on aligning IT with strategic objectives through four key layers: Business Capabilities, Information Capabilities, Technical Capabilities, and Governance Capabilities. This methodology provides a structured process, methods for aligning with business goals, and resources for managing the EA, all aimed at enabling organizations to deliver business value by framing architecture around their ability to achieve strategic goals.

Key Components and Approach

Gartner's approach shifts the focus from systems and processes to the organization's ability to deliver value through its capabilities. The framework emphasizes:

Business Capabilities: The fundamental abilities and functions of the business that are necessary to achieve strategic objectives.

Information Capabilities: The capacity to manage, process, and leverage information to support business operations.

Technical Capabilities: The underlying technology platforms and infrastructure that enable the business and information capabilities.

Governance Capabilities: The processes and structures for overseeing and directing architecture development and implementation to ensure alignment and control.

Benefits of Gartner's Framework

Strategic Alignment: It directly links IT decisions to strategic business objectives by focusing on capabilities.

Business Focus: Its business-centric nature makes it highly effective for securing board-level sponsorship and communication.

Simplification: It provides a simplified way to discuss architecture in terms of business value.

Integration: It integrates naturally with portfolio management and funding decisions, ensuring that IT investments are aligned with strategic priorities.

How to Utilize the Framework

Structured Process: Use the framework to guide the EA process through its various steps and methods.

Alignment: Ensure that architecture initiatives align with and support the organization's stated business goals.

Dynamic Management: Regularly update the architecture to adapt to evolving business needs, keeping the organization responsive to market changes.

Leverage Tools: Utilize enterprise architecture tools that allow for the capture of interrelationships between various artifacts (people, processes, information, technology) to build models that represent the enterprise's future state.

AL-3.6

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

⟲ AL-3.6.1 Info

Zarf Relevant concepts in considerations

Risks, Gaps & Ambiguities (AK-1):

- Complexity & overhead: The model is ambitious and multi-dimensional. Without careful scoping, it can become overwhelming, hard to apply in real projects.

- Ambiguity & lack of concrete rules: While many principles are presented, some rules (how to move diagonally, recursion boundaries, orchestration) are expressed more aspirationally than operationally.

- Steep learning curve: It requires familiarity with systems theory, lean, Zachman, recursion, fractals. Teams without exposure may struggle.

- Risk of over-generalization: In trying to cover "all systems," it may lose specificity for particular domains, details may have to be imposed externally.

- Value integration is subtle: Embedding human motivations (safety, fame, etc.) is powerful, but translating that into system constraints or design decisions may be tricky or subjective.

- Which vs Why trade-off: The replacement of "Why" with "Which" is philosophically interesting, but it may de-emphasize deeper purpose or normative grounding in favor of decision logic. Some domains still need a sense of why to anchor direction.

- Practical application / tooling missing: The page is conceptual; applying it in real community, organizational or software design may require additional templates, governance, tooling.

The end of the hierarchical organisation in the scope of decision making

In the information age, centralized decision-making becomes a bottleneck.

Alberts/Hayes argue that information-rich environments demand empowered actors at the edge who can interpret, decide, and act without waiting for top-down directives.

Dismantling traditional hierarchies challenges entrenched power structures, cultural norms, and comfort zones.

But the payoff, greater innovation, ownership, and responsiveness—is transformative.

Its a human-centered philosophy for leadership, collaboration, and organizational design in the 21st century.

There are strategic goals by “Power to the Edge” (Alberts/Hayes)

- Decentralized Decision-Making: Shifting authority from central command to the edge of the organization—where real-time information and action intersect.

- Agility and Adaptability: Empowering individuals and teams to respond quickly to dynamic environments.

- Trust-Based Networks: Building systems where collaboration and shared awareness replace rigid hierarchies.

The tacticals for adapting the strategy:

- From Management to Mastery: The idea that leadership is not a formal role but a personal journey, empowering individuals at the edge.

- Facilitators over Bosses: Replacing traditional managers with facilitators or rotating team leads mirrors the shift from centralized control to distributed leadership.

- Trust and Autonomy: Emphasizes trust and dialogue over hierarchy—core tenets

Nature as a Model: References to ecosystems (e.g., fish schools, bird flocks, forests) reinforce the idea that decentralized systems can be highly adaptive and resilient.

Dismantling traditional hierarchies challenges entrenched power structures, cultural norms, and comfort zones. But the payoff—greater innovation, ownership, and responsiveness—is transformative.

Bringing it to life: Map Your Value Streams, Build a Facilitation Cadre, Layers in Feedback Mechanisms.

A glimpse beyond: Nature-Inspired Networks, Dynamic Governance (Explore lightweight “policy as code”), Human-Tech Co-evolution (Experiment with AI assistants that surface context and risk at the edge).

By weaving these tactics into your own context, you transform abstract strategy into everyday muscle memory—ultimately unlocking that human-centered, responsive organization the information age demands.

The challlenge in the operations is adaption to the tactics.

Sometimes it is a natural adatpive change by the way the operational work is done.

The operational work however is a result of education, learning, training.

The crux of the challenge lies in translating strategic tactics into everyday operational behaviors, especially when those behaviors spring from formal training, ingrained habits, and learned processes.

To make adaptation more than a “one-off” shift, organizations must weave continuous learning and real-time feedback directly into the flow of work.

- Embed Learning in the Flow of Work

- Microlearning Moments

- Deliver bite-sized tutorials, videos, or checklists at the point of need (e.g., via mobile apps or digital dashboards).

- Tie each micro-lesson to a tactical shift (e.g., “How to run a rapid A3 experiment” or “Facilitation prompts for daily huddles”).

- On-the-Job Apprenticeship

- Pair less experienced operators with rotating “tactical champions” who co-solve real problems.

- Encourage shadowing and peer-led debriefs immediately after an adaptation is tried.

- Digital Twins & Simulations

- Use lightweight, scenario-based simulators to let teams practice new tactics in a risk-free virtual environment.

- Enable rapid “what-if?” iterations so lessons learned inform the next real-world cycle.

- Create Continuous Feedback Loops

- Real-Time Metrics & Visual Controls

- Surface leading indicators (cycle time, decision latency, experiment throughput) on shop-floor or digital war-rooms.

- Use simple “traffic-light” signals or Kanban boards to spotlight where the new tactics are stuck or succeeding.

- Rapid PDCA Cadences

- Shorten Plan-Do-Check-Act cycles from monthly to weekly (or even daily) so teams can adapt within days, not quarters.

- Document small wins and failures in a shared repository for cross-team learning.

- Voice of the Edge

- Empower frontline teams to propose tactical tweaks and vote on the most promising ones.

- Route their insights directly into leadership forums to keep strategy grounded in operational reality.

- Cultivate a Learning Culture

- Communities of Practice

- Form cross-functional cohorts around each new tactic (e.g., “Lean Experimenters Guild” or “Edge Decision Network”)

- Host regular show-and-tell sessions where practitioners demonstrate how they applied the tactic and what they learned.

- “Training as a Journey,” Not an Event

- Replace one-off workshops with a structured curriculum that combines e-learning modules, coaching clinics, and peer reviews over months.

- Award digital badges or rotating leadership roles to spotlight mastery of each tactic.

- Leader as Learning Sponsor

- Have executives and managers attend the same micro-learning and simulation sessions as their teams.

- Encourage them to coach, unblock, and publicly celebrate the adoption of new behaviors.

- Align Incentives and Accountability

- Edge level metrics

- Tie metrics directly to tactical adoption (e.g., “Edge teams reduce approval latency by 50% this quarter”).

- Review these metrics in every retrospective, pivoting the tactic or the support model as needed.

- Safe-to-Fail Experiments

- Architect “innovation sprints” within operations where teams can trial unorthodox approaches without penalty.

- Debrief failures candidly—treat them as data to refine the next iteration.

- Knowledge-Capture Rituals

- Make frontline retrospectives mandatory after every major operational shift.

- Store structured learnings (what worked, what didn’t, what’s next) in a searchable knowledge base, tagged by tactic.

Select one operational area (e.g., procurement, customer support) and launch an integrated adaptation program: microlearning, feedback loops, community forums, and metrics.